Having PCOS taught me how to advocate for myself

Here’s how I learned to trust myself and insist on better care

TW: discussion of weight and BMI

When I was 15, I was diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS. It had taken about a year of doctor’s visits and testing to be officially diagnosed. It had been two years since my last period, and my pediatrician was concerned about my “overweight” BMI (I now know that BMI is a flawed measurement and that my weight was just fine). I was tested for thyroid disease and diabetes, but my tests came back normal. It wasn’t until I went to an endocrinologist that my hormone levels were tested—sure enough, my testosterone levels were elevated, and I was diagnosed with PCOS. I guess this also explained the major peach fuzz that was occupying my upper lip.

PCOS is a hormonal disorder that can cause ovarian cysts, excess hair growth, and irregular periods. It can also lead to infertility, metabolic dysfunction, and more. I’ve lived with this incurable disorder for over a decade, experiencing a number of disruptive symptoms along the way. Though I would never choose to have PCOS, it has made me a better advocate for myself and for others. While I was certainly lucky to be diagnosed early—many folks don’t find out they have PCOS until much later in life—I have not had the easiest time managing my symptoms. For the first seven years after my diagnosis, my periods were accompanied by horrible side effects, like intense cramping, bloating, and more. In high school, I used to shove my books into my stomach to relieve the pressure and dull the pain.

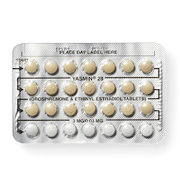

For a couple years in college, I would get the “period flu”—every time I got my period, I had intense flu-like symptoms (I know, the name is really clever). One weekend, I was so exhausted from this “period flu” and trying to maintain my class and work schedules that I slept for about 24 hours straight. Throughout this time, I tried four different brands of birth control pills and multiple regimens (e.g., taking 2 or 3 consecutive packs), yet none of these treatment plans worked for me. I felt like the Goldilocks of birth control, except if Goldilocks never liked any of her options and kept getting kicked in the uterus by the three bears.

The frustration I felt was compounded by the challenge of finding the right provider. The endocrinologist who first diagnosed me was constantly overbooked, leaving me in the waiting room for hours. My next several providers were a number of gynecologists in a women’s health practice. Each visit lasted maybe ten minutes, and I never saw the same provider more than twice because of scheduling difficulties. This meant that every year, I had to retell my story, explain again why the pill regimen I was on wasn’t working (and why the ones I had tried before it didn’t work), and be told that I needed to give it more time. This also meant that I had to listen to the same “just lose weight” spiel, as if it were that simple, as if I wasn’t trying.

I usually left my appointments feeling irritated and dejected. I hated feeling sick every month and being gaslit into thinking I wasn’t doing enough to help myself. But with every appointment and new provider, I became a better advocate for myself. When I was asked if I was sure my symptoms were that bad, I didn’t waver. When a treatment wasn’t working for me, I learned to insist on trying something new instead of “giving it another few months.”

Thankfully, my providers finally started to listen. Four years ago, I stopped taking the pill and had a hormonal IUD inserted, stopping my period and all the awful side effects that came with menstruating. No more period meant no more cramping, no more bloating, no more period flu—finally, this Goldilocks stopped getting kicked in the uterus.

I’m certain my persistence was not the only reason for this change in treatment. I am a white woman, and our health care system is riddled with racial bias. No amount of self-advocacy is going to change this systemic issue, and many people have a much more difficult time getting the health care they need, often with devastating consequences.

I’d love to say that my PCOS is fully under control now that I have an IUD, but that is not the case. I’m still struggling with some of my original symptoms (remember that pesky peach fuzz?), along with a couple new ones that come with additional treatments. In the last few years, I’ve come to realize that my mental health has been greatly impacted by this condition—people with PCOS are more likely to experience depression and anxiety and I unfortunately deal with both. Additionally, I was recently diagnosed with androgenic alopecia, a form of hair loss caused by too much testosterone, and now use both topical treatments and a daily eight-pill regimen to reverse it. Thankfully, it was caught early, and I started out with thick, voluminous hair (just ask the kid who used to stick pencils in it in middle school). But I’d be lying if I said I didn’t struggle with this new symptom.

I’m also coming to terms with the fact that my negative experiences managing my PCOS in a fatphobic society have left me with complicated relationships with food, exercise, and my body. I’m still “overweight” according to the BMI chart, but I’ve learned that BMI and weight are not good indicators of health, and the size of my body doesn’t mean I’m unhealthy. In fact, my bloodwork indicates otherwise.

As I continue to navigate the reality of living with this disorder, I know how to trust my experience and advocate for myself. I am a huge proponent of trusting science and the medical community—especially during a pandemic—but I also know that providers are human beings and human beings are flawed. So, while they may be the experts in their field, I am the expert on myself. Lived experience is important and valuable, and I will remind every provider I meet of this fact.

How do you feel about this article?

Heat up your weekends with our best sex tips and so much more.